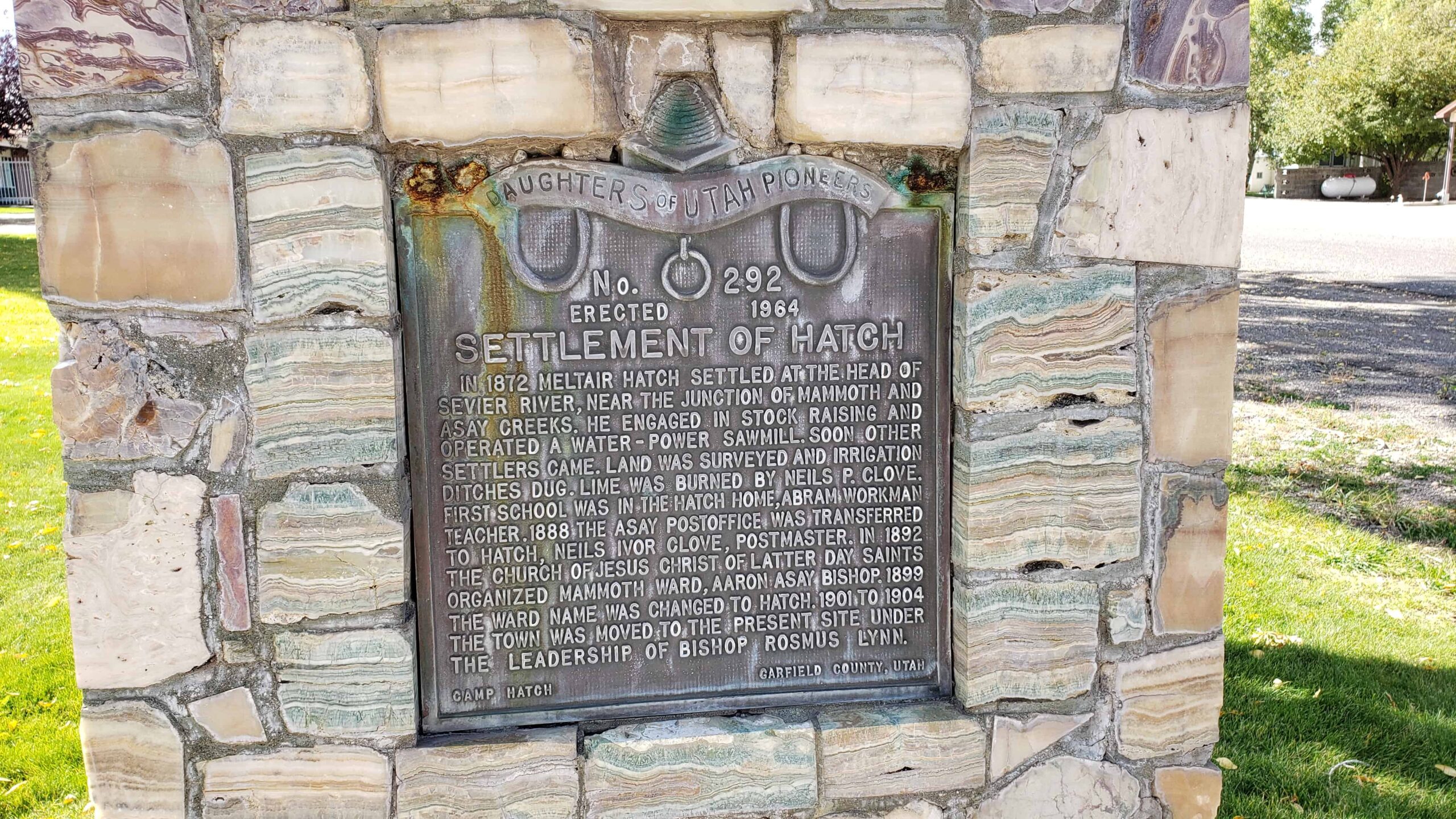

In 1872, Meltair Hatch embarked on a significant journey, settling at the head of the Sevier River near the junction of Mammoth and Asay Creeks. His endeavors in stock raising and operating a water-powered sawmill marked the beginning of what would become the town of Hatch. The initial settlement attracted other pioneers, leading to the surveying of land and the construction of irrigation ditches. One notable early contribution was by Neils P. Clove, who burned lime essential for building. The first school in Hatch operated out of the Hatch home, with Abram Workman serving as the teacher.

By 1888, the Asay Post Office was relocated to Hatch, with Neils Ivor Clove as the postmaster. The community’s growth was further solidified in 1892 when The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) organized the Mammoth Ward, led by Bishop Aaron Asay. The ward was renamed Hatch in 1899, reflecting the town’s growing identity. Between 1901 and 1904, under the leadership of Bishop Rosmus Lynn, the town moved to its present site, laying the foundations for the modern-day Hatch in Garfield County, Utah.

Extended Research: Early Challenges and Settlement

The origins of Hatch are deeply rooted in the broader efforts of LDS Church leaders to establish new communities in the western United States. In 1867, Meltiar Hatch, alongside his two wives, Permelia and Mary Ann, were called to settle the Dixie Mission in Eagle Valley, an area now part of Nevada. At the time, settlers believed they were still within Utah Territory. However, the redefinition of state boundaries in 1866, confirmed by surveyors in 1869, placed them in Nevada. This prompted Meltiar to consult with LDS Church President Brigham Young, who advised relocating to the Sevier River area, where better conditions for their livestock awaited.

Following this directive, Meltiar moved Mary Ann and Permelia’s sons to Panguitch, Utah, in the spring, followed by the rest of the family. The burgeoning community of Panguitch saw the establishment of a co-op, which amassed a significant herd of livestock. The co-op’s decision to relocate the herd 20 miles south led to the creation of a ranch near the confluence of Mammoth Creek and the Sevier River. Meltiar and his son managed this new enterprise, constructing a log home and corrals, thus laying the groundwork for what would become Hatch.

Mary Ann played a crucial role at the ranch, providing meals for ranch hands and welcoming newcomers. The Hatch home soon became the center of community life, hosting school sessions and LDS Church services. As the community grew, the area known initially as the Co-Op Ranch transitioned to Hatchtown, eventually shortened to Hatch. By 1880, the settlement had approximately 100 residents.

Water: A Lifeline and a Challenge

As with many small agricultural communities in the semi-arid West, Hatch’s survival depended heavily on water. In October 1901, the Upper Sevier Reservoir Company embarked on constructing a large dam to secure irrigation water for Hatch, Panguitch, and the surrounding areas. While the dam was intended to bring stability, concerns about its structural integrity emerged by March 1903. The Salt Lake Tribune reported fears that the dam might not hold, a concern validated on May 19, 1903, when the dam broke. Although the immediate impact on Hatch was minimal, the loss of water posed a significant challenge.

Efforts to rebuild the dam commenced in May 1907, with state engineer Caleb Tanner anticipating completion by spring 1908. However, construction delays extended the project’s timeline, culminating in another catastrophic event on May 25, 1914. The Ogden Daily Standard reported this as the “biggest dam break by far in the history of Utah,” with the release of approximately 14,000 acre-feet of water. The break destroyed over 15 homes and left 75 people homeless, with reports indicating that up to 300 residents of the Upper Sevier Valley, including those in Hatch, were displaced.

Resilience and Modern-Day Hatch

Despite these early setbacks, the residents of Hatch demonstrated remarkable resilience. The community gradually recovered, and life returned to a semblance of normalcy. Today, Hatch is a tranquil town, offering several quaint restaurants and motels that cater to travelers along scenic US 89 and visitors to nearby Bryce Canyon National Park. The town’s history, marked by determination and community spirit, continues to be a source of pride for its residents.

Sources

- Hatch Historical Committee. Wandering Home: Stories and Memories of Ira Stearns Hatch, Meltiar Hatch, and John Henry Hatch and their Wives and Children, with Historical-Genealogical and Biographical Data on Their Ancestry and Descendants. Provo, Utah: Community Press, c1988.

- Linda King Newell and Vivian Linford Talbot. A History of Garfield County. Salt Lake City, UT: Utah State Historical Society; Garfield County Commission, 1998.

- “Danger of Dam Breaking.” Salt Lake Tribune, 27 March 1903. Link.

- “Reservoir Breaks near Panguitch in This State.” Ogden Daily Standard, 26 May 1914. Link.

Primary Sources

- “Bids Are Asked for Sevier River Dam.” Inter-Mountain Republican, 29 May 1907. Link.

- “Hatchtown Dam Ready in Spring.” Inter-Mountain Republican, 17 December 1907. Link.

- “Hatchtown Reservoir to be Ready in March.” Inter-Mountain Republican, 15 January 1909. Link.

- “Panguitch Notes.” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 26 October 1901. Link.

- “Reservoir Gives Way.” Salt Lake Tribune, 20 May 1903. Link.

- “Utah Settlers Flee for Their Lives When the Hatchtown Dam Breaks.” Salt Lake Telegram, 26 May 1914. Link.

Through this historical lens, the settlement of Hatch exemplifies the challenges and triumphs of pioneering life in the American West, with its story continuing to inspire future generations.